Derailed on the Orient Express : Long, Painful Career of DeCinces Ends Amid Indifference in Japan

- Share via

The 19-year professional baseball career of Doug DeCinces, a career that included a World Series, 1,505 hits and hundreds of rousing moments, ended this summer. It didn’t end with a tearful speech or an emotional cap-waving farewell. And it didn’t end with 40,000 fans standing and saluting one of baseball’s best third basemen.

As a matter of fact, when it ended, even DeCinces wasn’t standing. He was lying on his side on a patch of soggy AstroTurf in Tokyo, numbness in his legs and scorching pain rippling through his back as 35,000 fans who didn’t really know Doug DeCinces from Doug Flutie sat in unemotional silence.

Just another rich and aging American ballplayer with another imagined injury on another drizzly, neon Tokyo night. It could be worse, most of the fans thought. It could be one of our players crumbled up on the carpet of the infield.

“Foreigners are simply not well-liked over there,” DeCinces said. “It was always obvious. They call us gaijins , and the word is not a positive way to refer to foreigners. It’s slang with a derogatory meaning. The Japanese don’t want us living there. It’s OK for them to come to our country to live, but it’s not OK for us to go there to live.”

The pain and the frustration and the homesickness welled up inside DeCinces. Two days after the injury, he and his family were on a plane heading back to Southern California. The Great Japanese Experiment had ended. And so had DeCinces’ days of playing baseball, days that stretched back 30 years to the first time an 8-year-old boy from Northridge stepped to the plate in a Little League game.

A week after his return from Japan, medical examinations at Centinela Hospital in Inglewood revealed a herniated disk in DeCinces’ oft-injured back. Another disk protruded from his spine. The word from the doctors was absolute. The party was over. He officially announced his retirement earlier this month.

“My time was up,” DeCinces, 38, said. “My back has bothered me for so many years, but somehow I always found a way to come back, to rest and let the pain go away. And this time, it was a different pain, a worse pain. I lost control in my legs and that scared me.

“In 1980, after going through another back injury, I just decided that God gave me this body and I would make the best of it and that He would let me know when it was time to stop playing.”

DeCinces never imagined, however, that the message would be delivered to him in Japan and that it would come while he was wearing the uniform of the Yakult Swallows.

DeCinces’ ailments began during his junior year at Monroe High. Years later, a doctor would discover a healed compression fracture in a lower vertebra. The doctor pinpointed the year of the fracture as 1966, DeCinces’ junior year in high school.

DeCinces kept playing, however, and was drafted by the Orioles. After his fourth minor league season, he was told to get ready for the jump to the major leagues. And at roughly the same time, his back problems flared up again.

“I knew I couldn’t tell anybody,” he said. “All those bus rides through the minor leagues made it pretty tough on me, and we didn’t have great medical care in the minors at that time. But I just couldn’t let anybody know I was having these problems. My chance at the major leagues was right there and the last thing I wanted people to know was that I had a bad back.”

DeCinces eventually replaced Brooks Robinson at third base in Baltimore, and the young infielder endured several seasons of abuse from fans and the media. Regardless of how well DeCinces performed, they all said, he was not Brooks Robinson.

Of course, Brooks Robinson never had a spinal cord that appeared to have been hastily assembled by unskilled laborers.

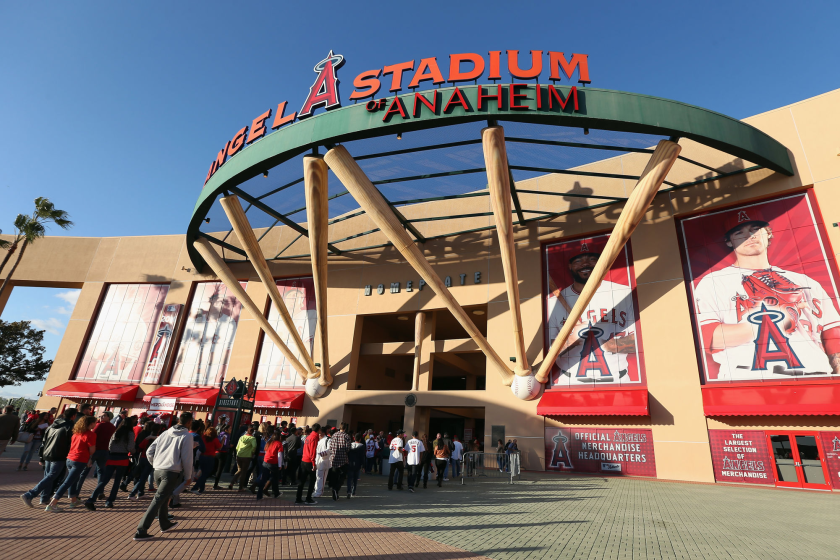

During the 1979 season, DeCinces spent 10 weeks in a hospital, most of that time in traction. He had more problems in 1980. He was traded to the Angels in 1982, and, after a spectacular first season, missed 50 games in 1983 because of the pain in his back. Each season after that was a season of pain for DeCinces, but in 1986 he pounded 26 home runs and drove in 97 runs, leading the Angels to the American League West championship.

Then came The Series.

In one of the most dramatic league championship series ever, the Angels came within an out of reaching the World Series, losing in spectacular fashion to the Boston Red Sox. Despite his contributions during the season, DeCinces was offered only a 1-year contract for the following season, complete with a hefty pay cut.

“It was strictly a take-it-or-leave-it offer,” he said. “The Angels would not even talk to me about it.”

Mostly because he didn’t want to uproot his family again, DeCinces said, he took it. But the 1987 season was to be the most frustrating and mentally painful of his career. With a week left in a disappointing season, the Angels cut DeCinces loose. General Manager Mike Port did it with no public announcement and with very few words to DeCinces.

“Mike called me in before a game,” DeCinces said, “handed me a piece of paper and said, ‘Here’s your unconditional release.’ I waited for him to say something else, but he never said another word. I said my piece to him, and I left. Later I thought to myself, ‘No wonder this team has never won a World Series and it’s no wonder they probably never will. Not with that kind of a person in charge.’ ”

DeCinces played the final week of the season with the St. Louis Cardinals, then entered the free-agent market. He said he had generous offers from the New York Yankees and Oakland Athletics but began to consider retirement. Then, however, came a blockbuster offer from Japan.

“The money certainly had a lot to do with it,” he said. “Plus, I felt I could still play baseball on a daily basis, as a starter. That might not have been the case in the major leagues. So I figured if I was going to move my family away from our home for a while, we might as well try something very different.

“Believe me, it was different.”

DeCinces, who hit 237 homers and had 879 RBIs in the major leagues, replaced former Atlanta Braves slugger Bob Horner on the Yakult Swallows’ roster when Horner returned to the major leagues with the Cardinals. DeCinces had talked with Horner and other ex-major leaguers about life in Japan, but their words did not prepare him for the changes.

“The year got stranger as it went,” he said. “I went in with a very open mind, ready to accept almost anything. But I had no idea what it would be like.”

On the field, the pressure from the fans and the swarming Japanese media was brutal, DeCinces said, comparing every Japanese game to a World Series game. And the pressure on the few Americans was overbearing.

“They expect so much of you,” he said. “They actually expect a home run every time you come up. When it doesn’t happen, resentment grows real fast. And among my teammates and coaches, things were strange. They asked me to teach them things, but they didn’t really want to learn. I’d show them something, and they’d be practicing it another way the next day. If it wasn’t the Japanese way, it’s the wrong way. They just don’t want to be told that they are teaching something the wrong way.”

Despite those problems, DeCinces said he could have survived the season with a smile on his face. But the problems he and his family--including 14-year-old son Tim and 9-year-old daughter Amy--encountered away from the ballpark turned his smile into a frown in a big hurry.

“The feeling that they don’t particularly like foreigners comes across every day,” he said. “It wasn’t too bad for me because some of them recognized me as a ballplayer. But for my family, it was unbelievable. We never got used to the crowded conditions and how the people treat us on the streets. They can be quite rude. They bump you and grab you and push you out of the way so they can go through a door first. My kids and wife were not treated well at all.

“We could sense the hostility every day. People would stare at us and laugh at us. After a while it really gets on your nerves. My final opinion was that the Japanese are just not a great bunch of people.”

DeCinces had made up his mind that he would not return for another season, even if he was offered a Nebraska silo full of yen. The final injury to his back on a wet Japanese infield was simply the punctuation mark. He has now embarked on a new career in the construction business, joining his father in a successful Van Nuys-based operation that develops commercial and industrial property.

“I feel good about my career,” DeCinces said. “I don’t like the way it ended and I don’t like the unprofessional manner in which the Angels handled my final season, but yet I still think of myself as an Angel. I spent more time with the Baltimore Orioles, but I’ll always think of myself as an Angel.

“I hope people remember me as a winner and a competitor who gave everything he had when it came time to go out on the field. I always felt my teammates had respect for me, and that meant a lot. I never felt I truly reached my optimum ability because of my back problems, and it was very frustrating at times. But I believe the medical problems made me stronger mentally and made me able to handle the bad times.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.