The Next ’12 Angry Men’? Well, the Bidding Was Furious

- Share via

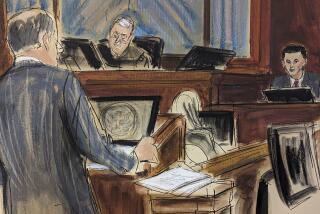

Hollywood is falling all over itself in a rush to make the next generation of courtroom dramas. Out is the fictional whodunit, good guy vs. bad guy variety. In is the true-life, criminal as victim case. Witness its thirst in adapting the Menendez and Bobbitt trials as entertainment.

Now, joining those screaming-headline stories is the case of . . . Martin Kaplan?

Telephone lines recently heated up among agents, directors, producers and studios over who would win the film rights to an accounting of Kaplan’s paradox-ridden Manhattan trial--the subject of a first-person article in the New Yorker by journalist-juror William Finnegan titled “A Reporter at Large: Doubt.”

The 17,000-word story ran in the Jan. 31 issue; its sale to United Artists was completed less than three weeks after publication.

In his piece, Finnegan recounts why he voted to help convict Kaplan of an assault and robbery that took place at the Astor Place subway station in Manhattan last year, despite his gut feelings that the case had holes. The two men who were robbed and beaten seemed certain that Kaplan was one of their three muggers.

But following Kaplan’s conviction and at his sentencing, Finnegan encountered one of the convicted felon’s ex-girlfriends in the elevator and was struck by the very different impression she conveyed in person than the low-class one she made on the witness stand. She was, in fact, the multilingual daughter of well-educated Chileans and supported herself as a free-lance translator for various government agencies.

His conversation with the woman spurred him to reinvestigate, on his own, witnesses’ accounts of where Kaplan was the night of the crime and other facts he found had been skewed or omitted by attorneys for both sides. It also caused him to write an account of his first-time jury experience for the New Yorker--refashioning the tone of his piece midstream as events and interviews affected his beliefs.

Overall, the crux of Finnegan’s article is not that the letter of the law wasn’t observed in Kaplan’s arrest, trial and conviction. He believes it was--and says so at the end of his piece. More, it was that evidence that either was not admissible in court (like Kaplan’s prior record) or was incomplete would have weakened the prosecution’s case and perhaps changed the outcome of the trial.

Kaplan’s alibi, supported by witnesses, was that he had been eating at an East Village cafe. Police said he was caught with traces of blood on his hands. The victims had been bloodied too.

But Kaplan’s attorney, not wanting to prejudice jurors, kept from them the knowledge that Kaplan was a heroin addict with a long rap sheet, who often injured himself breaking into cars to support his habit. His record also showed a pattern of stealing, but only one arrest for assault, which was dismissed. In collect phone calls from prison, Kaplan told Finnegan that he bled from “an abscess on my arm where I had been sticking a needle into it.”

As the author said in an interview: “My further conversations with alibi witnesses and with Kaplan have pushed me deeper into doubt that he did it. It’s not that I’ve come up with new evidence or novel arguments . . . it’s just that things keep meshing so that (his) alibi makes as much or more sense than the prosecution’s theory of the crime.”

Not exactly “12 Angry Men,” but close enough, said ICM agent Irene Webb, who successfully brokered the deal.

Fittingly, it was “Prince of the City’s” Academy Award-nominated writer Jay Presson Allen who read Finnegan’s piece and, according to both UA production vice president Jeff Kleeman and Finnegan himself, initiated its sale to Hollywood by pal UA President John Calley. Though UA was the victor--reportedly agreeing to pay in the low six-figure range if the movie is produced--it first had to outbid such rival producers as Gale Anne Hurd, Lynda Obst and Tony Bill, among others, as well as Universal Pictures, sources said.

Finnegan, 41, known more for his reporting on South Africa and Central America, said he was “delighted” to have sold his first property to Hollywood. He has heard from neither attorney nor the judge. Kaplan, Finnegan said, nitpicked about one detail, while his alibi witnesses said they “liked the piece.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.