Doing War With Super Germs

- Share via

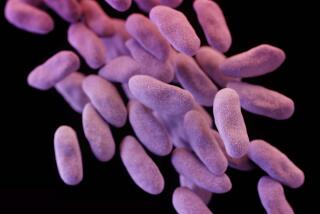

For years, staph bacteria have been storming our medical lines of defense, and now there’s evidence that the potentially deadly germ may have evolved to overwhelm the most powerful antibiotic approved for use, the drug vancomycin. According to the Centers for Disease Control, a Japanese infant stricken by a new strain of staph bacteria represents the first known case of a human whose infection cannot be killed by vancomycin.

The agency says staph bacteria can be blamed for the deaths of up to 10,000 hospitalized Americans each year. Fortunately, just as our medical bag seems to be running out of effective pills, promising new cures are on the horizon. In recent months several genetically engineered antibiotics have, in limited human trials, demonstrated their potential to wipe out the hardiest bacteria, even the newly discovered strain in Japan.

Most conventional antibiotics work by binding themselves to bacterial cells and stopping them from building the structures they need to survive. But antibiotics work slowly, giving bacteria time to mutate and develop resistance. Antibiotics can also confuse bacterial cells with human cells and lay siege to both.

By contrast, the advanced antibiotics now under development, such as the genetically engineered cationic peptides, kill the bacteria on contact, striking only after pinpointing a unique signature.

Without government help, however, cationic peptides will take years to develop for mass use. Congress, now in the process of earmarking public funds for research into particular diseases, should note that its funding levels for new antibiotics have remained relatively stagnant while the need for such drugs has become increasingly acute.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, says the CDC report on the rapacious new staph should be “a shot across the bow to citizens, legislators and scientists to accelerate research into antibiotic-resistant microorganisms.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is also in the picture. Officials say the USDA should consider prohibiting farmers from adding low doses of certain antibiotics to cattle feed. The practice reduces the amount of food that livestock need to reach marketable weight, but it also promotes the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Scientific evidence indicates the bacteria can be transferred from livestock to humans.

Consumers can fight bacteria in their homes by understanding common dangers like the potentially deadly salmonella, which can be transferred from raw meat to vegetables when the same knife is used to prepare both.

In pressing the effort to find new antibiotics, scientists and lawmakers should need no motivation beyond looking at the case of the Japanese infant struggling against bacteria we thought we could control.