Political books the presidential candidates should be reading

Alexie is a poet and writer whose books include “Reservation Blues” and “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.”

For Romney:

Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species,” so he’d learn that humans have advanced because of compassion and not competition.

Emily Dickinson’s “Collected Poems,” so he’d learn that faith and doubt are fraternal twins.

Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” so he might understand why 90% of black folks will not be voting for him.

Leslie Marmon Silko’s “Almanac of the Dead,” just to scare the spit out of him about brown-skinned immigrants.

John Kennedy Toole’s “A Confederacy of Dunces,” to give him a sense of what it means to be funny and serious at the same time.

For Obama:

A dictionary so that he could look up the definition for “progressive.”

James Baldwin’s “Giovanni’s Room” — though I’d guess he’s already read it, I’d like him to place this novel in the context of black evangelical homophobia.

James Welch’s “Winter in the Blood,” to remind him that, yes, there are still Indians in this country.

Patricia Highsmith’s “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” because I suspect he doesn’t read enough mysteries. And also to make him think about the relationship between wealth and fraud.

Leslie Marmon Silko’s “Almanac of the Dead,” also to scare the spit out of him about brown-skinned immigrants. (Alexander Gallardo / Los Angeles Times)

The Times’ book staff asked writers, historians and cultural observers for their suggestions on books that could help Romney or Obama govern effectively over the next four years.

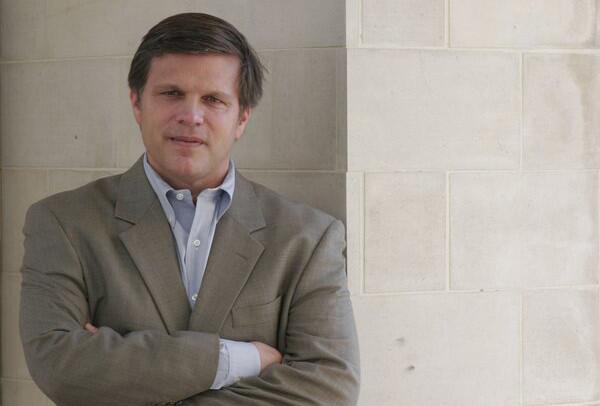

Brinkley is a professor of history at Rice University and the author of many books, including “Cronkite.”

Mark Fiege’s “The Republic of Nature”

A brilliant analytical recounting of U.S. history with the environment serving as the leading change agent. By linking ecology to the improbable rise of King Cotton, the Salem witch trials, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and even Brown vs. Board of Education, Fiege artfully demonstrates how presidential decisions automatically have an environmental impact on daily life.

Steve Coll’s “Private Empire”

A penetrating investigative exposé on the philosophy of Exxon Mobil (the largest, most powerful oil and gas company in America). The mask of Big Oil is ripped off in this outstanding hybrid of journalism and history.

David Crist’s “The Twilight War”

A sterling round-up study, full of wild anecdotes, about the troubled U.S.-Iran relationship. With allegations of Iran secretly aiming to develop nuclear weapons, this narrative is mandatory reading for any commander-in-chief.

Lizzie Collingham’s “The Taste of War”

A masterpiece of World War II history anchored around the essential interaction between food and strategy in the 1940s. Any president anxious for war needs to learn how hunger and famine anywhere in the world hurt the democratic cause. Without our great agricultural abundance, Collingham convincingly argues, America might have lost World War II.

Victor Cha’s “The Impossible State”

The best way to learn about the heinous real North Korea. It’s an enlightened policy saga about the enigmatic Asian nation state’s determination to be a world-class dictatorship. The Kim family dynasty proves to come as advertised — they’re a monstrous clan. An extremely impressive NSC-styled white-paper gussied-up to make a deeply insightful book. (Dave Einsel / Los Angeles Times)

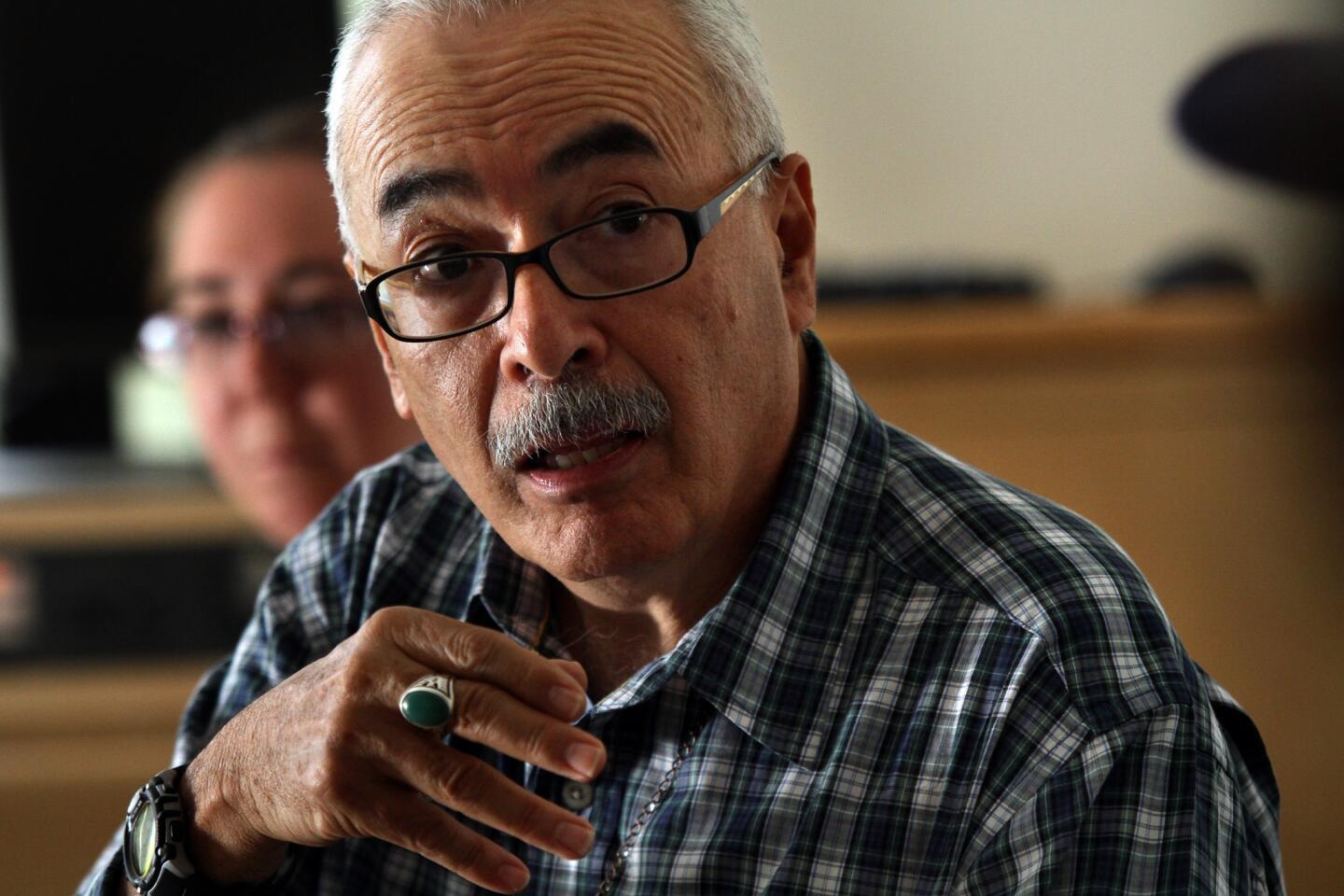

Herrera is California poet laureate and a professor in the department of creative writing at UC Riverside.

“The Marriage Artist” by Andrew Winer

Gets you closer to a rare painter-novelist such as Winer and to his masterful work of lyricism, Jewish histories and the complications of marriage, suffering and mystery. What I enjoy is the poetic flow and art of language and the intricacies, and unfoldings of things we do not want to talk about in today’s world politic and day-to-day experience: anti-Semitism, the Holocaust and its ongoing influences in contemporary life at its most intimate layers. And, yes, transcendence, is this possible?

“Crooked Cucumber: The Life and Zen Teaching of Shunryu Suzuki” by David Chadwick

Although Chadwick’s superb biography speaks of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, a pioneering teacher of Zen Buddhism in the Bay Area, during the 1960s and up to the time of his passing in the early 1970s, we are really learning how to walk gently — with our full lives — through crises, confrontation and incredible possibilities for change. Our time, perhaps? There is much to learn about his entry as a young boy into a Buddhist monestary in Japan to his voyage and founding of the Zen Center in the Bay Area and the establishment of the Tassajara Monastery in a new land and culture. How did he adapt to the Imperial expansionism of Japan? How could one humble man transform an entire way of life in the West Coast? What makes this book a bigger book than it seems to be at first sight?

“Emplumada” by Lorna Dee Cervantes

A classic in Latina letters. And Lorna, you need to know, is one of the most brilliant poets in the U.S. today. What can her poems do for us? They can escort us into the Latina and Latino condition and life experiences in ways that are not quick-step sociology- or demographic-speak; we need to touch the fire of race, gender and marginalization with 10-story-high creativity and insight. She speaks, in magnificent lyric and story, of a woman-family, warriors in their own right and the impossible role as scribe, an “emplumada.” We need the impossible scribes.

“Soul Calling: A Photographic Journey through the Hmong Diaspora” by Joel Pickford

One of the most illuminating, piercing and, yes, soulful, spiritual, let me say human portraits that I have seen of a people — the Hmong — that are part and parcel of our nation, yet I believe not in the center of our attention. Having spent many years in Fresno, I have come to know and partner up with Hmong poets, librarians and community organizers. This book inspires me. Pickford, daring, elastic and patient, with an ethnographer’s outside/insider camera-eye and pen, takes us deep into Laos villages and back to California, through exile, death, survival and new life — these are not mere words in the book, they are real-real.

“Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street” by Karen Ho

Wall Street—behind closed doors. Ho, a former investment analyst, employs the ol’ power tool of anthropology, that is, ethnography. Ho learns and unpacks the trade culture of the players, the “stories,” “talk,” “practices” and the “relationships” in private and public settings and finds something most alarming. Among other discoveries, to be a Wall Street agent, power resides in being “smart.” And “smart” has a lot to do with making “deals” that “impress” the honchos and that leave the rest writhing in the dust. Little is left to what we usually attribute to the vagaries of the economy. It seems that what you and I, and José and María Palooka call “the way things are” is more the way things are constructed by the “smart” ones on WS. I am taking notes and keeping my pesos in a basket.

“Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits” by Laila Lalami

“Illegals.” Undocumented immigrants. Wearing the hijab. Religion — culture and class. It is all here. Boating for the future from Morocco across the waters to Europe. Four characters — Faten, Halima, Aziz and Murad — with four dreams, separations, losses, transformations. I find these portraits of desire to be highly valuable. We need to discard stereotypes and stop and know the intimate lives of people and most of all, what “hope” is really made of.

“Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt” by Chris Hedges and illustrated by Joe Sacco

This is a stark, touching and almost tactile report-story on the “sacrifice zones” where lands and peoples have been pushed aside for bigger elite and corporate interests. Yet, somehow, the people do continue and do respond. With Pulitzer Prize-winner Hedges and the black-inked portraits and freeze-frames of Sacco, we partake in the incredible moments of private and public conversations. You and all of us are there—it is this moving. Even in the blown-off top of an Appalachian mountain or huddled in a symphony-like circle of voices at the start of the Occupy Movement at Zuccoti Park. You walk away a little changed, maybe—with a lot of insight. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Hochschild is a journalist and the author of “King Leopold’s Ghost” and “To End All Wars.”

“The Global Warming Reader,” edited by Bill McKibben

I’m tempted to make all five books on this list books about climate change, because it is the gravest challenge facing us on Earth — and both major presidential candidates hardly mention it. Time to get serious, boys.

“The Best and the Brightest” by David Halberstam

Some 60,000 Americans, and a vastly larger number of Vietnamese, died because of our hubris about our ability to reshape a distant part of the world to our liking. The final bill is not yet in for similar attempts to do so in Iraq and Afghanistan. A careful reading of this classic account of our Vietnam folly might discourage a president from trying the same thing in yet a new country.

“The Great Divergence: America’s Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do about It” by Timothy Noah

We now have one of the most unequal distribution-of-income patterns of any major country in the world. This, too, ought to be an issue on the campaign trail.

“Griftopia: Bubble Machines, Vampire Squids, and the Long Con That is Breaking America” by Matt Taibbi

Something else missing from campaign rhetoric: any talk of who belongs behind bars for getting us into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. Taibbi, one of the country’s premier journalists on this issue, introduces some of the villains involved.

“Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk” by Ben Fountain

The other books have few laughs, so, as a reward for reading all four, I’m going to assign the presidential candidates a novel. Raunchy, eloquent, dazzling, the entire action of the book takes place during a Dallas Cowboys game, as seen through the eyes of a shrewd, oversexed, traumatized 19-year-old Iraq war vet being paraded around the country on a closely-managed “victory tour” with his squad mates. Ben Fountain is marvelous: Few other American fiction writers today have this ambitious, tragic, hilarious and brilliant political eye. (Kim Kulish / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Smiley is the author of many novels, including “Private Life,” “Ten Days in the Hills” and “A Thousand Acres.”

“Why the West Rules, for Now” by Ian Morris

Seventy-thousand years of humans trying to wring a living from the earth have led to this election, and you gentlemen need to read about how two specific traditions, eastern Asia and Europe, have gone about rising, but especially falling. Every lesson Morris has to teach is a critical one, especially now, when, as he points out, the world as a whole is approaching a development “ceiling” that old empires have hit before. If these ceilings are not understood and dealt with, ruin ensues.

“Why Nations Fail” by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson

There are two types of economies, inclusive and extractive. Inclusive economies grow by spreading both the wealth and the political responsibility — England in 1689, for example. In extractive economies, the ruling class siphons off the wealth and kills the lower orders doing so — Spain in the New World, for example. The U.S. has mixed parentage on this score, and those who like the extractive economy have been gaining power for the last 30 years (“Government IS the problem”). See Ian Morris, above, for the probable endgame.

“American Nations” by Colin Woodard

The 11 cultures that coexist in the U.S., Woodard convincingly asserts, have different ideas about most values and most aspirations. Every so often, as during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, they form unstable coalitions and fight. The nations currently in the ascendant are extractive ones — Deep South (steeply hierarchical and unequal), Far West (dependent on oil, mining, ranching and corporations for wealth, dependent on the federal government for sustenance, and therefore resentful), and Netherlander (Wall Street, ‘nuf said). Several of the other nations (Left Coast, El Norte, Yankeedom) may be getting fed up and ready for the fight.

“Predator Nation” by Charles Ferguson

Ferguson is from San Francisco, which wouldn’t surprise Colin Woodard. He therefore has a lively sense of social responsibility, strong views about right and wrong, and is highly creative. In “Predator Nation” he lays out, with admirable verve and clarity, just who wrecked American banking, and who should be prosecuted and why. Ian Morris maintains that each civilization that finds itself approaching its biological, technological and teleological ceiling reacts in different ways. Ferguson understands that the American reaction of just letting it go accelerates collapse, of both the middle class, President Obama AND the upper class, Gov. Romney.

“L’Argent” (or, since Obama didn’t spend the Vietnam War in France, “Money”) by Emile Zola

We’ve been here before, and not too long ago. Zola, one of the most prescient 19th-century novelists, analyzed and depicted the system in his day, and is worth reading for both the similarities and the differences between the French Second Empire and the American current empire, in this case, the financial system. We are not so exceptional after all, and maybe both candidates need to understand that, even if they dare not mention it on TV. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

Straight’s new novel, “Between Heaven and Here,” will be published next month.

“Bulfinch’s Greek and Roman Mythology”

A Harvard man who moved back with his parents, Bulfinch never married and became a bank clerk so he could focus on his true passion: giving the world classic tales of myth. The Greeks believed their kingdom was the actual center of the earth, and all other nations were only considered in relation to them. Their major and minor gods and goddesses have fantastic, fanatical confrontations with themselves and with humans over land and love, etc., etc. And reading — or rereading — these will help the candidates remember how unimaginative and neurotic these battles continue to be when self-absorption rules.

“Fools Crow” by James Welch

Every time I give people this book, they say it changes the way they look at America. It was not America to Fools Crow, a young man from the Pikuni tribe — later his people would be called Blackfeet, and the land he knows by landmarks such as Woman Mountains and Singing Grass Creek, with gods like Coldmaker, and a distant, vague president called “White Man in Chief,” is being taken away treaty by treaty, acre by acre, with the guns every man, no matter what language he speaks, wants. The legends of this country, when there were not even states yet, are wondrous and melancholy and bitter in the foretelling.

“The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman” by Ernest J. Gaines

Jane is 9 when the Emancipation Proclamation is read, and though she’s then free, her life is worth nothing because she isn’t property. Her epic journey takes her only about 50 miles in a hundred more years, but her deadpan and often hilarious voice recounts the story of American history At a Reconstruction political rally that might remind the candidates of town halls now, Jane watches: “Most of the talk was about the Fedjal Gov’ment …The Democrats wanted the Yankees to get out so we could build on our own. The Republicans wanted the Yankees to stay. The Democrats said we wouldn’t have peace till the Yankees had gone. The Republicans said we didn’t have peace before they came there. The Republicans said every free man ought to have forty acres and a mule.” Illuminating, no?

“Winesburg, Ohio” by Sherwood Anderson

Here’s the land cleared and planted with cornfields where farmers work and grieve, where lovers lie in secret, where unhappy small-town men dream, the land when brick buildings are erected to make the small towns and big dreams, the streets where people hold onto their guilt, their burning need to be someone bigger, to leave the small town which is still held up as true America. When politicians talk about “real America” and “small-town values,” they might read this and realize how reductive that seems, how small towns are not “flyover” space but have their own mythologies.

“Between Two Worlds: The People of the Border” by Don Bartletti

Times photographer Bartletti’s book chronicles through photos taken during the 1980s and ‘90s the people from Mexico and Guatemala who gathered at the border waiting to cross, the lives they left behind and their existence at the edges of the wealthiest communities in Southern California. The men live in “spider holes” and caves at the edges of strawberry fields, and on terraces above freeways strung with night headlights. Has anything changed, or are the strawberries still red and waiting in the furrows, and the hands still pulling open plastic sheeting to reveal dawn?

“Dream Street” by Douglas McCulloh

“Dream Street” begins with a strawberry field in inland Southern California, cleared for a new housing tract, and really it is the best way for the candidates to end their reading. In this book we see how land becomes money, and a house becomes an investment rather than a home, built by an underpaid army of single-task workers who endure nails through their palms and employ their own 11-year-old sons to climb the rafters installing AC ducts. This is America right now. This is part of how we got underwater, as a nation, the distillation of every myth we believed in, and the idea that we could own any ground, how strawberries turn into foreclosure when nothing is really about home. (Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

Trombley is president of Pitzer College and the author of “Mark Twain’s Other Woman.”

“Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings”

Humanity, intelligence, despair, determination and belief in a greater good all come through in the prose of our most eloquent president. Facing a changing nation, a ruinous war, a generation of men lost, a destroyed economy, debates about race and rights, Lincoln had a practiced clarity of thought and a gift for expression that remains unmatched. His integrity, willingness to accept change while remaining elastic in his thinking while simultaneously withstanding intense political pressures to hold the party line makes him a role model for us all.

“The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain

A novel of American voices, in all their glorious variations of dialect, that tells the tale of a little boy lost trying to find a safe place along the banks of the Mississippi River. With strategic use of humor, Twain guides us through this most violent of narratives, laughing all the way, that explores child abuse, the ruthlessness of slavery, the nihilism of mindless violence, stereotypical gendered behavior, xenophobia and racism, and the dangers represented by established education and religion. When Huck lights out for the territory at the end, instead of referring to a true physical territory, perhaps Twain is hinting at an interior, metaphysical one and that we should free ourselves.

“Waiting for Nothing” by Tom Kromer

The best book you have never heard of. Writing in the aftermath of the Great Depression, Kromer’s memoir describes his struggle for survival during a time when there was no state or federal relief. A searing tale that humanizes the too often invisible and hidden faces of poverty. His United States is a hostile, brutal place where people are exploited and cast aside. His is a cautionary tale about the responsibilities and failures of humanity and society.

“Song of Solomon” by Toni Morrison

Layers of magic, folk tales, classical and biblical allusions, all of which work to underscore a coming-of-age narrative, a relationship fable, the African American experience, and life in these United States. This is lyricism at its finest with the smallest details having the greatest of impact. It is a song of resilience that reminds us of both our past and the promise of a not-yet-realized future.

“Regarding the Pain of Others” by Susan Sontag

In keeping with the tradition of women intellectuals like Margaret Fuller and more contemporaneously Gloria Steinem, Angela Davis, Elaine Kim and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Sontag’s essays detail the essences of human existence from image to aesthetics, to illness, to war and ultimately death. There are no easy answers. The emphasis is always to look below superficial meaning to deconstruct the reasons for thinking the way we do and divining whether we should continue to do so. (Glenn Koenig / Los Angeles Times)