Eleven facts you might not know about California’s missions

Zorro was born at a

Figuratively speaking, that is. Author Johnston McCulley’s first story about the black-masked crusader, published in 1919, was titled “The Curse of Capistrano” and set at Mission San Juan Capistrano. The first Zorro movie followed soon after.

This revelation (on Page 71) is just one among many sacred and secular nuggets to be found in “The California Missions: History, Art, and Preservation” (Getty Publications, 276 pages, hardcover, $39.95), a new coffee table book that’s both scholarly and, in the words of historian Kevin Starr, “sumptuous.” It has 170 color illustrations, 100 more in black-and-white, enough to give your fourth-grader a substantial advantage when time comes for that build-a-mission-with-Popsicle-sticks assignment. (It lacks, however, a picture of Zorro. And there’s not much practical information for a traveler.)

Of course the missions story is tricky to tell, given the countless souls the friars intended to save, the tens of thousands of Native American lives lost, and the romantic fondness so many people have for the look of those old buildings. In their quest of photos, sketches and paintings, authors Edna E. Kimbro (who died in 2005), Julia G. Costello and Tevvy Ball, working for the Getty Conservation Institute, used sources as diverse as the

Here, only slightly sensationalized, are 10 more facts from the book, along with some images.

-- Christopher Reynolds, Los Angeles Times staff writer (Courtesy San Juan Capistrano Mission / From The California Missions, Getty Publications)

1. Before Alta

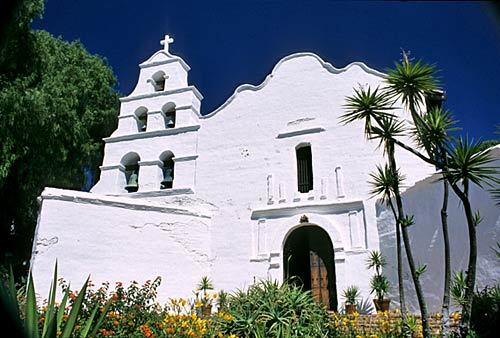

Those churches, many of which endure, were built from 1697 to 1767, when Spain expelled the Jesuits from Baja California. (Page 14) (G. Aldana / From The California Missions, Getty Publications)

2. The main mission man in Alta

Junípero Serra, the Spanish-born Franciscan friar who led the expansion of missions into California, was already 56 when he reached

4. The first mission tourist may have been

No, not the naughty novelist. This Henry Miller, from Northern California, was a little-known artist who rode by mule in 1856 to visit and sketch all 21 missions (Page 37). Several other painters followed, and photographer Carleton Watkins set himself a similar mission in the 1870s and 1880s. Writer Robert Louis Stevenson spoke up for mission preservation in 1879. But it wasn’t until after “Ramona” in 1884 that a broad preservation movement gained momentum. (Courtesy Garzoli Gallery / From The California Missions, Getty Publications)

Advertisement

5.The biggest mission was in Oceanside.

Though the average mission settlement’s population of attached native “neophytes” rarely topped 2,000, San Luis Rey de Francia, in what is now Oceanside, grew quickly to a population of nearly 3,000. In the late 1820s, operations were said to include 60,000 head of cattle (Page 23). (Carleton Watkins / From The California Missions Getty Publications)

6. We can thank the Spanish for introducing Chinese fireworks to

The fireworks came, of course, amid all sorts of other good and bad baggage brought by missionaries and soldiers, including the following: influenza, smallpox, typhoid, syphilis, horses, cattle, incense, candles, corn, squash, guitars, trumpets, mirrors, bells, silk and iron (Pages 32 and 33). (Bill Dewey / From The California Missions, Getty Publications)

7. While

In 1750, before the missions reached Alta California, this region was home to an estimated 300,000 Native Americans. By 1855, that figure had fallen to about 50,000 (Pages 14 and 53). (Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art / The California Missoins Getty Publications)

8. Most of the state’s mission churches are latter-day replacements.

Of the 21 mission churches that existed in 1832, only 10 original buildings have survived. Of those, four are made mostly of adobe (

Advertisement

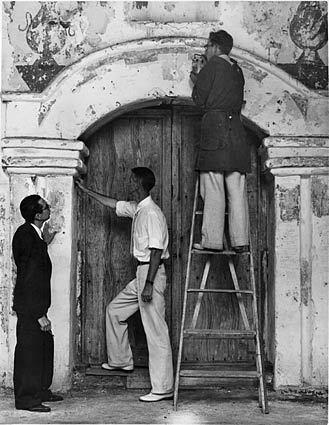

9. Once, these places were awash in crazy colors.

In their effort to clean up the crumbling old sites, the missions’ rescuers often covered or removed old murals, applying plain paint jobs in their place. Generations of fourth-graders, touring the sites as part of their