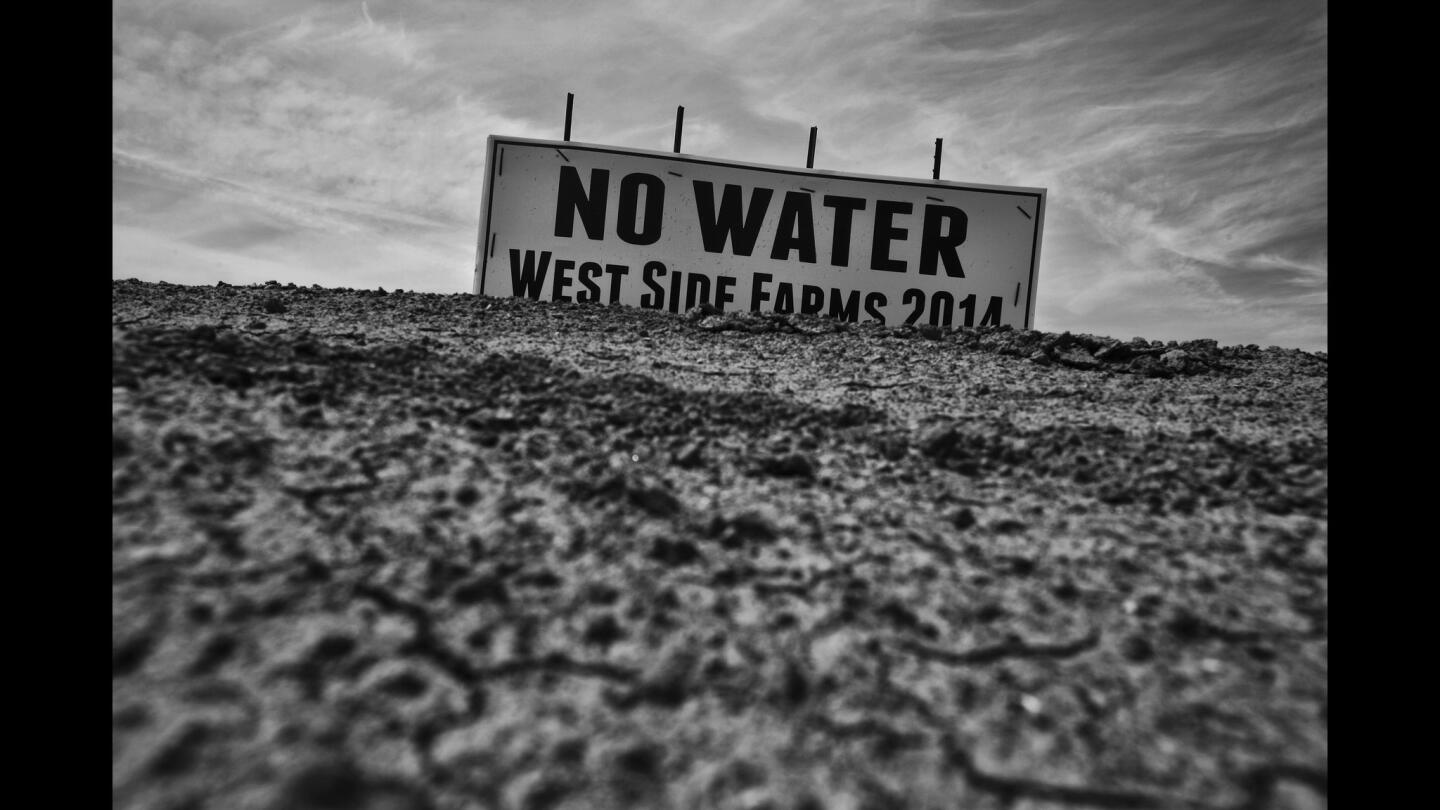

Drought yields desperation in Huron, Calif.

Drought has ravaged towns in the western San Joaquin Valley. A patch of farmland bakes under the sun near the town of Huron. Huron has seen its population move on to other states and cities where there is more work. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

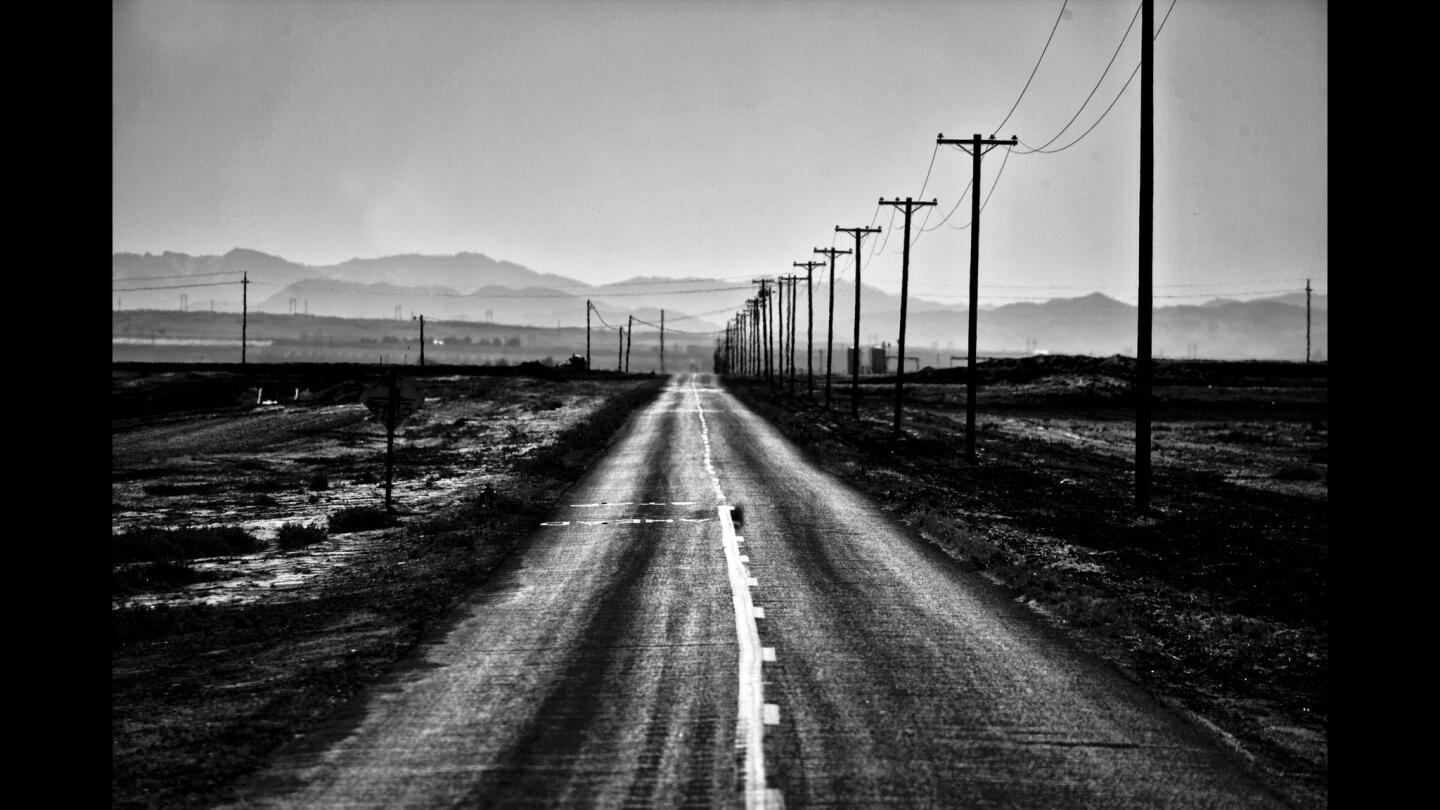

The slowly unfurling disaster of California’s drought is catching up to those living in Huron. Each day more families are leaving for Salinas, Arizona, Washington -- anywhere they heard there were jobs.

A worker stands in a field planted with garbanzo beans, one of the few fields around drought-stricken Huron that is actually being farmed. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Field workers wait for a meal after finishing a shift outside of Huron, a Central Valley town hard hit by the drought. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

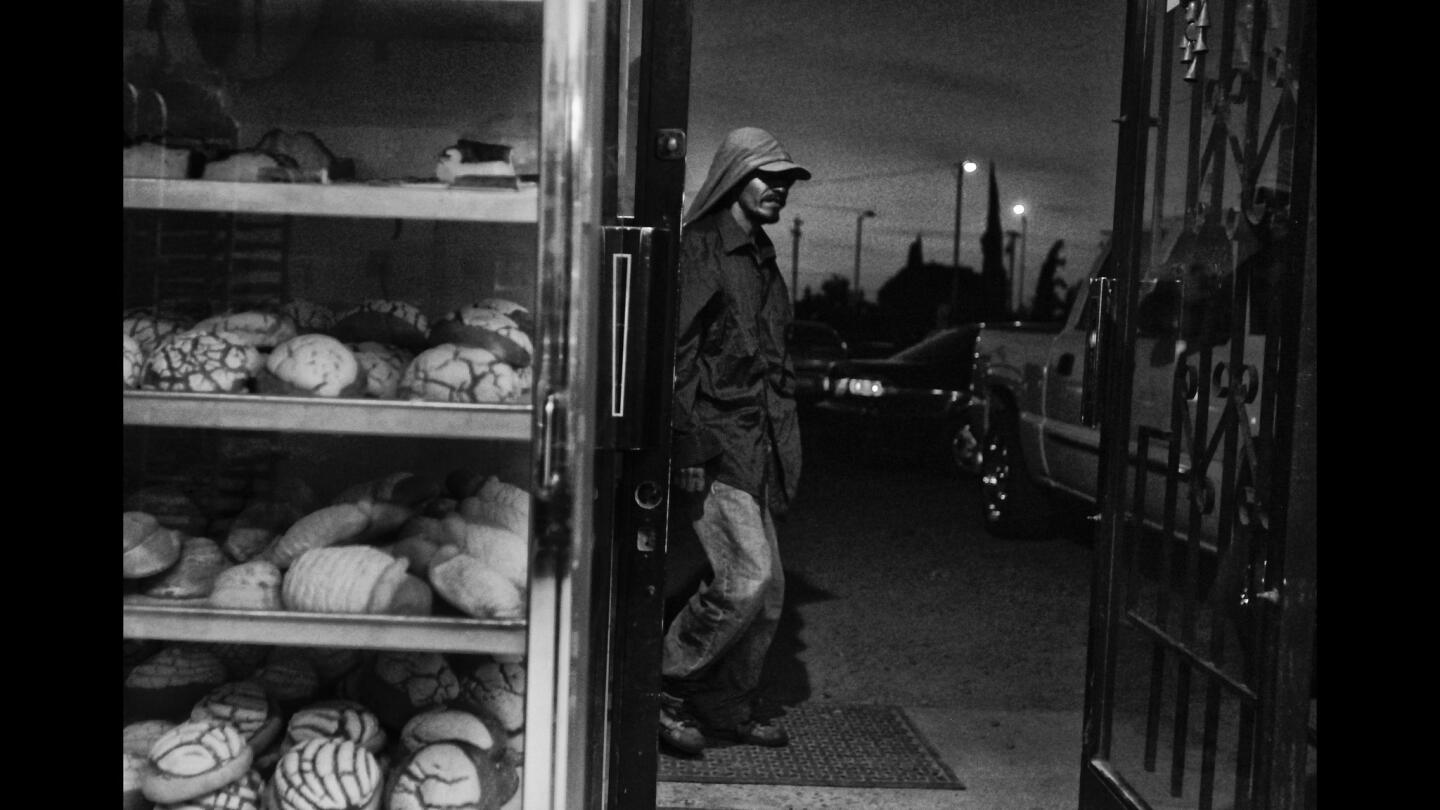

Huron, an agricultural town in California’s Central Valley, is being ravaged by the drought. A woman waits for employers in the pre-dawn hours outside a bakery. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Field workers pick garlic outside of Huron, a Central Valley town hard hit by the drought. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Huron, an agricultural town in California’s Central Valley, is being ravaged by the drought. Men wait for employers in the pre-dawn hours outside a bakery. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

A memorial stands at the edge of the Central Valley town of Huron. Many of the nearby fields are fallow. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

A flock of sheep moves past the few workers tending a field of almond trees in Huron, Calif., a farming town where there was once enough work for multiple crews of 20. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

In a third year of California’s drought, farmworkers such as Hector Ramirez are lucky to find a few days of work a month in the San Joaquin Valley, where fields lie dry and devastated. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Fieldworker Francisco Galvez, 35, sits on the floor of his sparcely furnished home as a Mormon missionary speaks with his family. In Huron, religion has sprouted where crops have not. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

When Francisco Galvez’s wife, Maya, found out she was pregnant with the couple’s seventh child, she apologized to her husband. “She told me she is worried for me because there is no work,” he said. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

At a local “carniceria,” or butcher shop, in Huron, prices have risen during the drought since there are no other shops or towns for at least 15 miles. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Fieldworkers once could line up work ahead of time, but now gather in the early morning at a local “panaderia,” where they can no longer afford to buy bread or coffee, to wait for a contractor to come and bark an offer. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Huron faces a $2-million deficit, and only about 1,000 people in a town with a permanent population of 7,000 are registered to vote. Of those, only some 200 actually do. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Carlos Garavan sits on a bench in the center of Huron, where stray dogs roam the streets. Garavan once ran for the Huron City Council, but no one has declared for the two currently open seats -- including the incumbents. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Many businesses along Huron’s main commercial corridor, Route 269, have folded and been boarded up. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

“We’ve been having less problems downtown,” said Huron Police Chief George Turegano. “People have less money in their pocket. They’re saving it to move to the next town, the next job.” (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

The hourly rate for day laborers in Huron has plummeted to $8 an hour. But they must also pay for their transportation to the fields, usually between $8 and $12 a day. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Each day more Huron families, including permanent residents, are leaving for Salinas, Arizona, Washington -- anywhere they heard there were jobs. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Since the days of the Dust Bowl, towns like Huron have been the places where trouble hits first and money doesn’t last. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

An agricultural vehicle makes its way down Huron’s main street. Without the rains, even California’s vast system of buying, selling, pumping and moving trillions of gallons of water from the Sacramento Delta to this dry, clay-bottom plain wasn’t enough to keep Huron working. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Workers install a new piping system to a 2,200-foot-deep well they recently put in. Waiting periods for new wells are upwards of one year and can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Though this is the third year of drought, fieldworker Antonio Chavarrias believes it’s just the beginning of the hardships. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Fieldworker Francisco Galvez is determined that the one sacrifice he won’t make for his family is leaving them. Once before when times were hard, he went alone to Texas to work. He was gone more than three years. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

“It’s going to get worse,” fieldworker Antonio Chavarrias says of the drought. “They’re not planting. Think what it will be like at harvest.” (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)