Chinese abandon 12th century apartments in favor of more modern lifestyles

Corn ears dry from balconies inside a tulou in southeastern China. The structures are in an agricultural region that grows corn, tea, bamboo and citrus and other fruits. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

Since the 12th century, ethnic groups in Fujian province have protected themselves inside tulou, rammed-earth apartments facing a communal courtyard. Amid rising incomes, residents are abandoning the tulou way of life.

Qingxing tulou has partnered with a Seattle-based Chinese American family, which is seeking to preserve the tulou through a nonprofit-type model. Friends of Tulou invites small groups of scholars and students to stay from time to time in about 50 spare guest rooms. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

A boy plays outside a tulou, while corn dries in the background. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

A small tulou sits on a river bank in Hongkeng village in southeastern China’s Fujian province. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

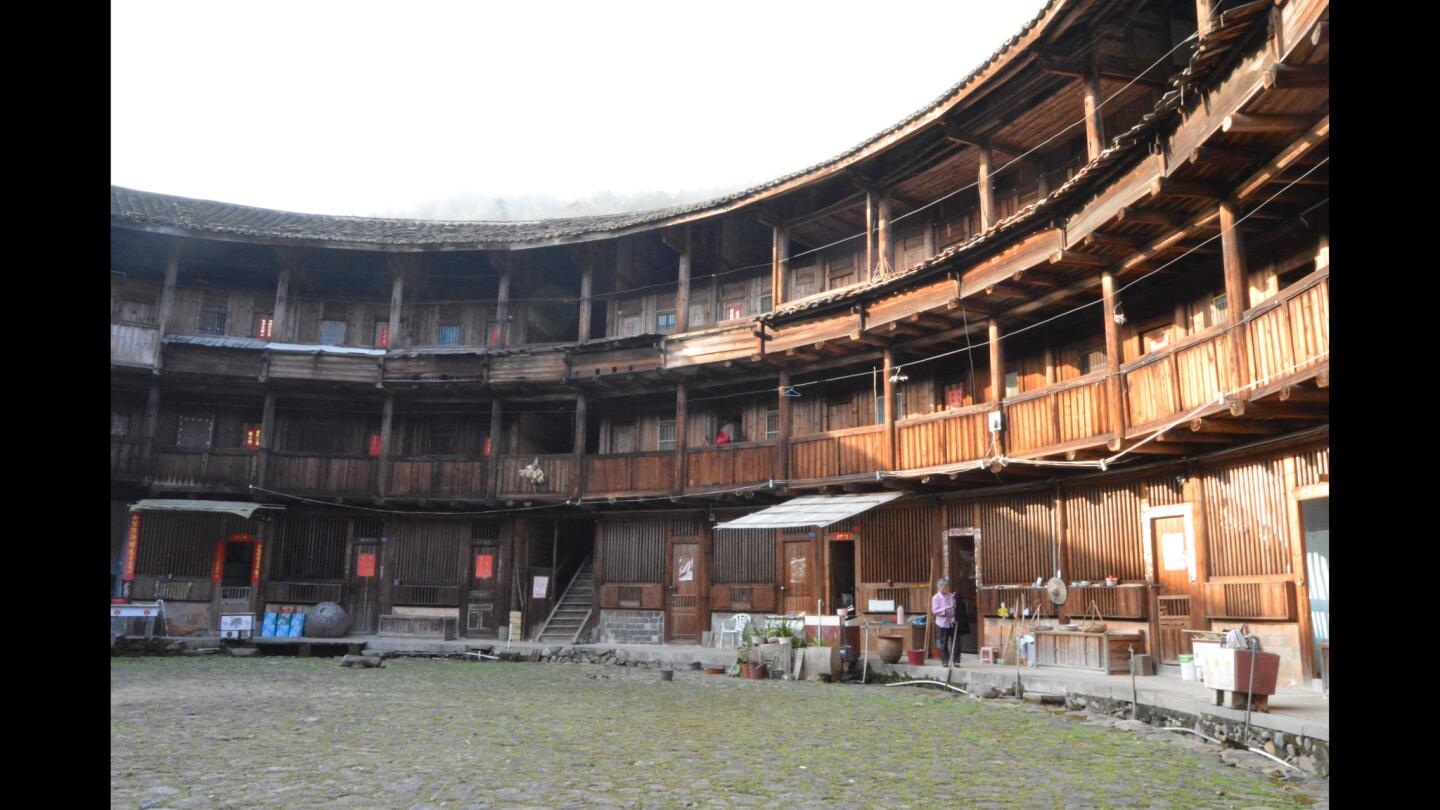

The inside of Qingxing tulou. The building, erected between 1950 and 1961, is home to a dozen or so mostly elderly residents. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

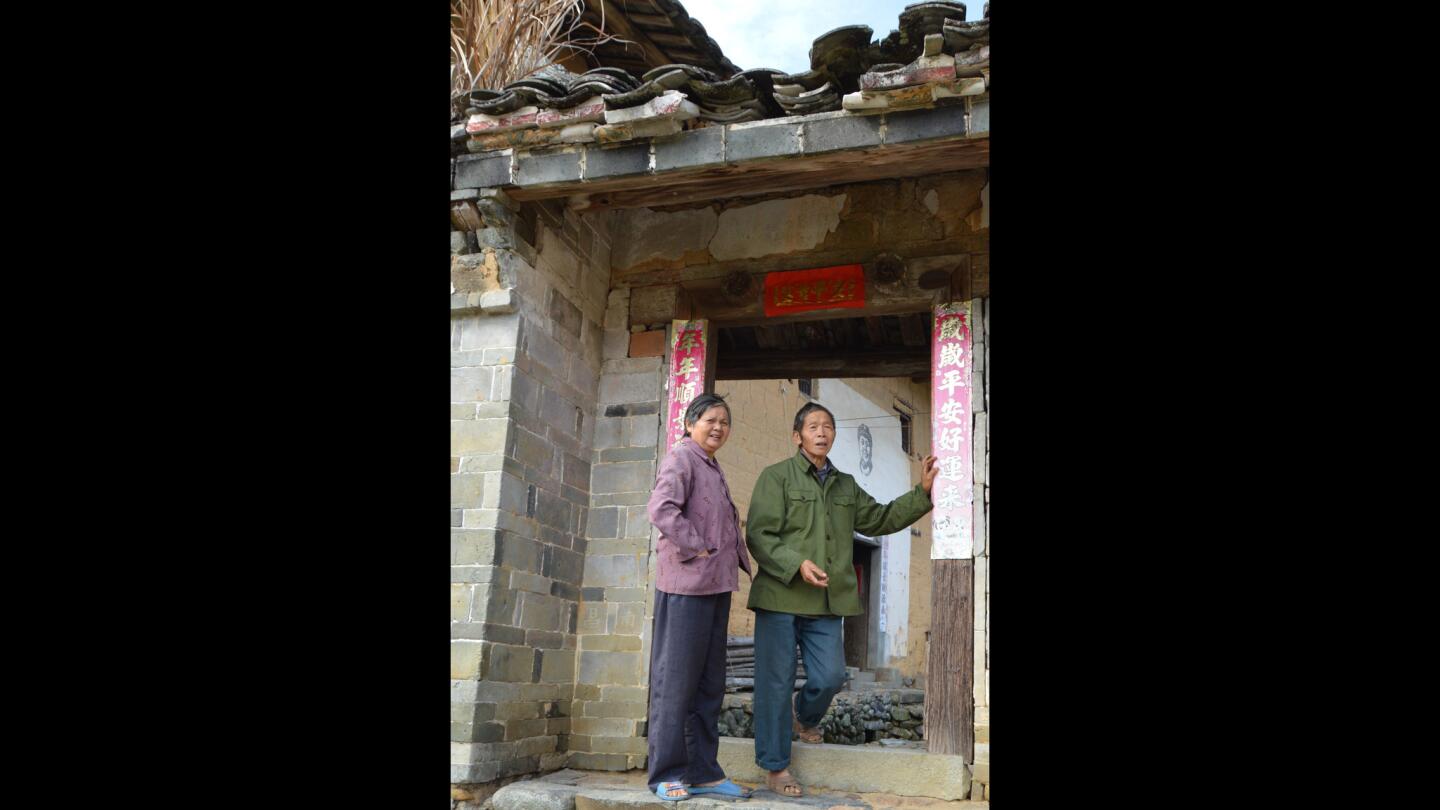

Huang Maoyou, 67, left, and Xiao Dashi, 73, cling to the simple life in their 400-year-old tulou. They’re the only residents left in the two-story building, which has more than a dozen rooms. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

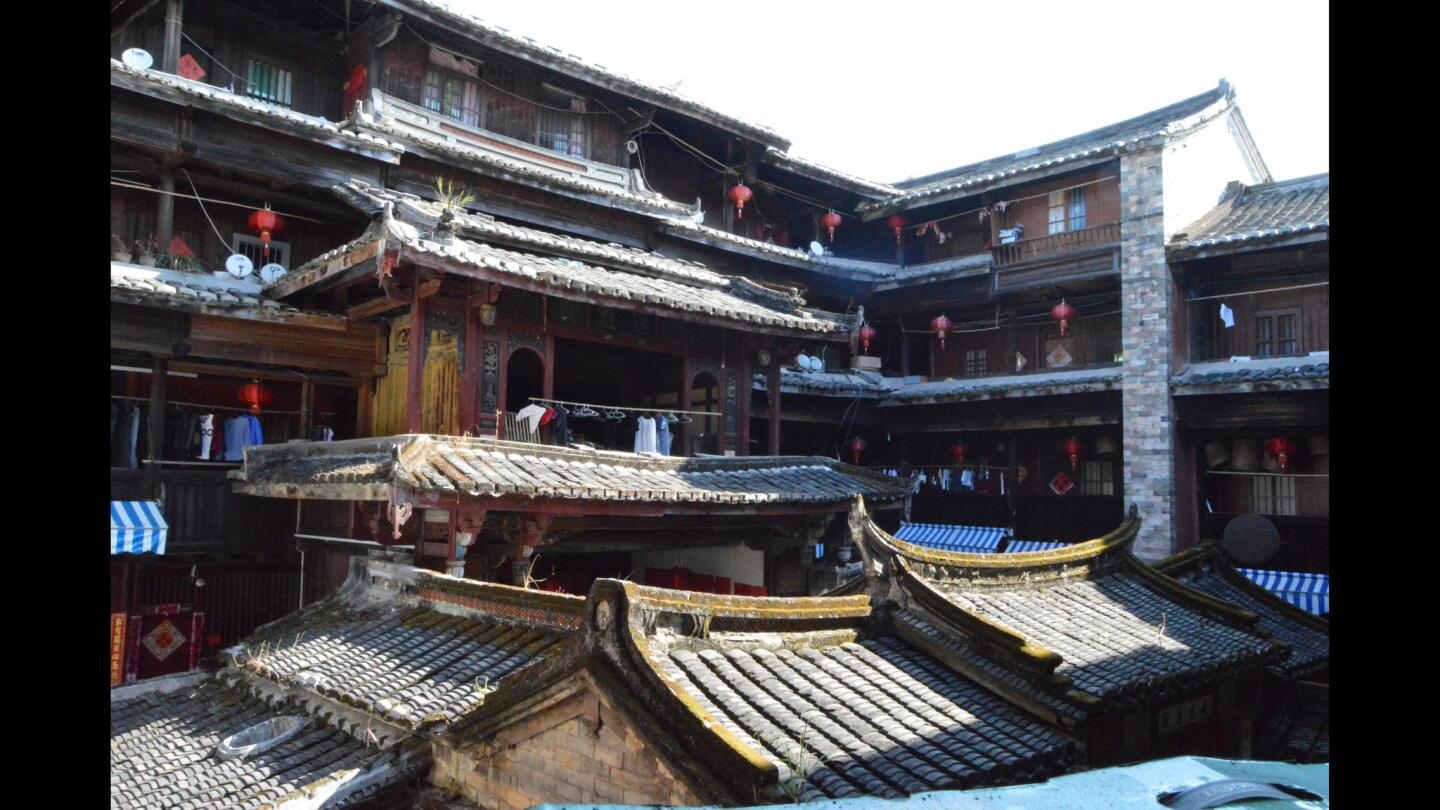

The Fuyu tulou in Hongkeng village in Fujian province has 160 rooms. One wing with 19 rooms has been converted into a hotel, and 50 other clan members occupy the rest of the structure. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

Interior balconies of a tulou bear red lanterns and laundry. Some apartments even have amenities such as satellite TV. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The interior courtyard of a tulou is a communal space for cooking, working, drying laundry and more. Here, a man uses a knife to shave bamboo and repair a basket. (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)

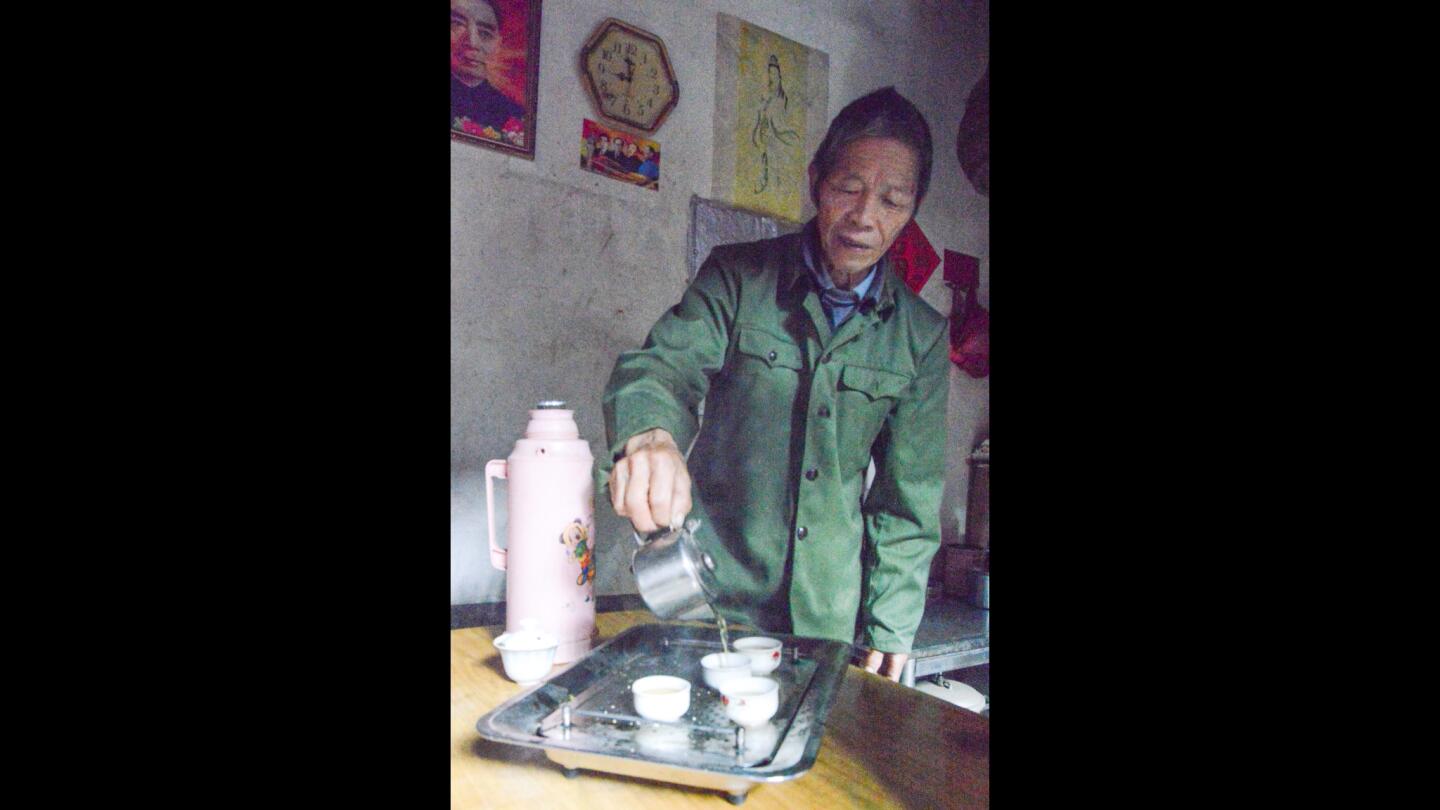

Xiao Dashi, 73, pours tea for visitors to his tulou. “My sons and daughter have all moved to the city, but I can’t stand to live there,” said Xiao, who refuses money from his visitors. “I can’t read, and I prefer to stay here and work in the fields.” (Julie Makinen / Los Angeles Times)