Mexico’s drug war

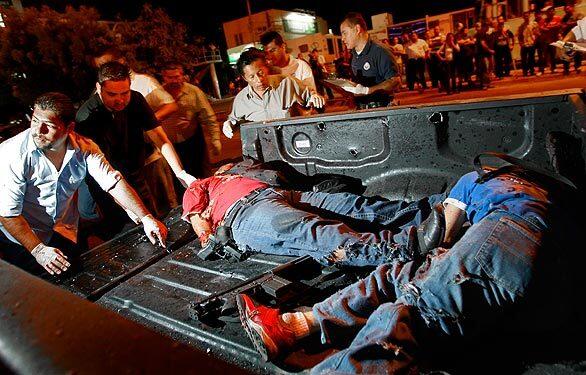

Weapons lie in the bed of a truck alongside the bodies of two plainclothes police officers in Culiacan slain in November violence. Shootings, even of cops, are hardly investigated. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Relatives of the five officers gunned down in Culiacan run around the ambush scene screaming and crying while federal police officers guard the shooting site in the background. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

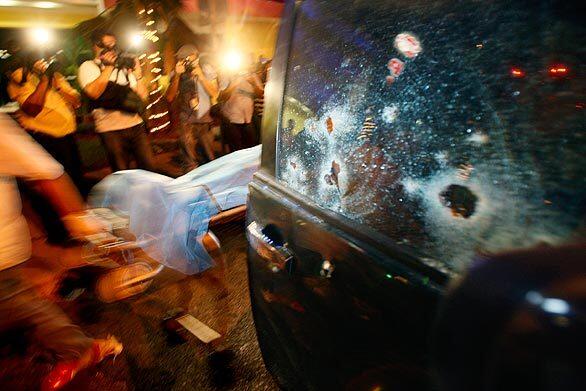

The body of a policeman is taken from the scene of the shootout in Culiacan. The assailants got away. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Relatives of police officers slain in an ambush force their way through police lines and stagger around the gruesome scene. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

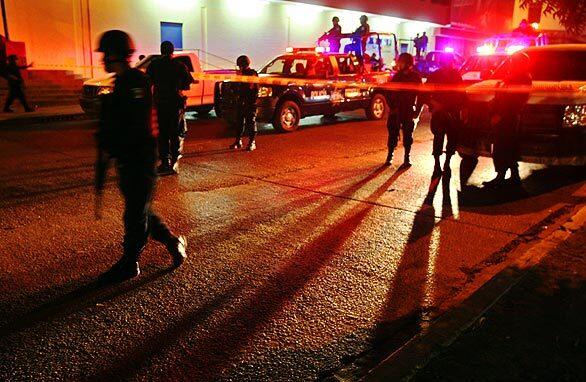

In central Culiacan, a Mexican federal police officer surveys the scene after the Nov. 19 shootout that killed five federal and Sinaloa state police agents. More than 100 police officers have been killed in Sinaloa this year, most of them gunned down. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Mexican federal police officers guard the scene of the ambush in Culiacan that left five police officers dead. Drug-related violence has killed more than 5,000 people in Mexico this year. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Members of a unit of the Mexican federal police load their gear onto a jet at the Culiacan airport. They are being being replaced by a fresh unit flown in earlier on the same plane, two days after the five officers were gunned down. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

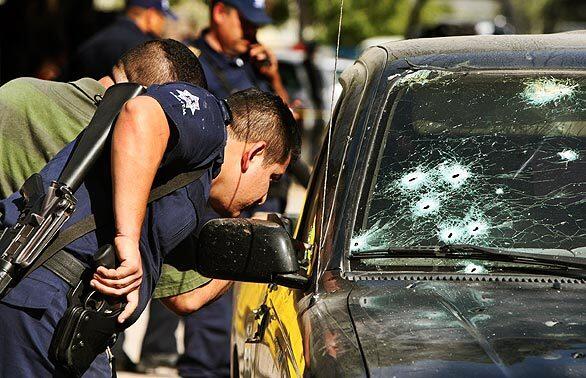

With a hand on his sidearm, a Culiacan police officer looks for victims in a bullet-pocked pickup truck. Neighbors had already taken the wounded or dead from the scene, the aftermath of an attack by a rival drug faction. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Neighbors gather in a Culiacan neighborhood to look at two vehicles shattered by automatic gunfire a half block away. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Women in Culiacan are left horrified by a shootout between rival drug dealers that left puddles of blood at their doorstep. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Anti-drug crusader Yudit del Rincon, a Sinaloa state legislator, once received a funeral wreath with her name on it. She is more careful these days about attacking individuals, but she is more determined than ever to challenge a doped-up status quo. “All society is contaminated,” she says. “We are being held hostage.... If we remain silent, where will we end up?” (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

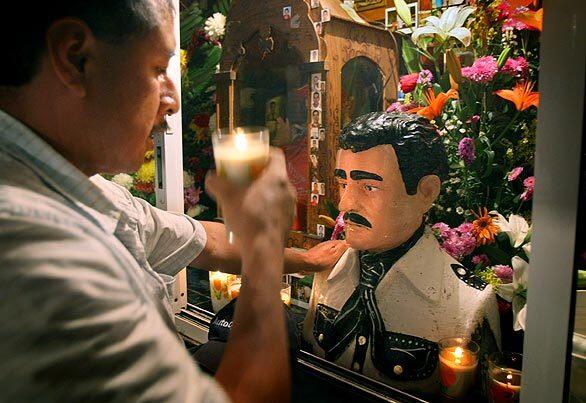

A man pays homage to a statue of folk hero Jesus Malverde, the “narco-saint” to Sinaloa’s drug traffickers. The shrine in Culiacan celebrates the bandit who was said to have given to the poor before being killed by authorities in 1909. On this night another man hoped that a prayer and donation would insure that his shipment of illegal drugs would make it to the United States. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

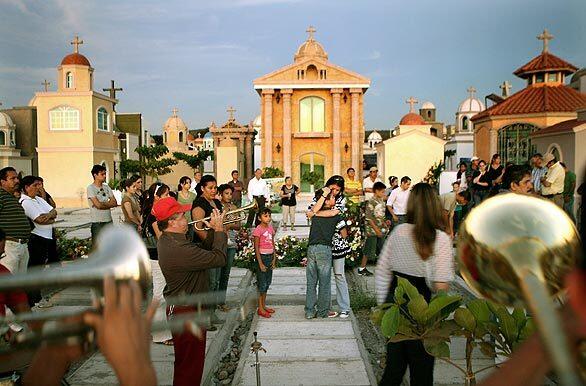

Relatives embrace and the band plays during a burial at a Culiacan cemetery. Many of those buried here were involved in the drug trade and died young. Families spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to erect mausoleums built with imported Italian marble, Corinthian columns and French doors. Lupito, Beta, Payan and dozens more take their journey to the afterlife accompanied by bottles of tequila or cans of Tecate. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Artist Jose Espinosa Moraila, 50, paints the ceiling of a mausoleum. In the background is a blown-up snapshot of the 32-year-old man interred in the crypt in the Culiacan “narco-cemetery,” where families spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to erect structures that adulate the life that put their relatives in their graves. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)